The Fulkerson Family Pages

Fighting Fulkersons, The Battle of King's Mountain

The American Revolution had not affected their remote area until now, but in the summer of 1780 the British had overrun much of the Southern states and were moving northward.

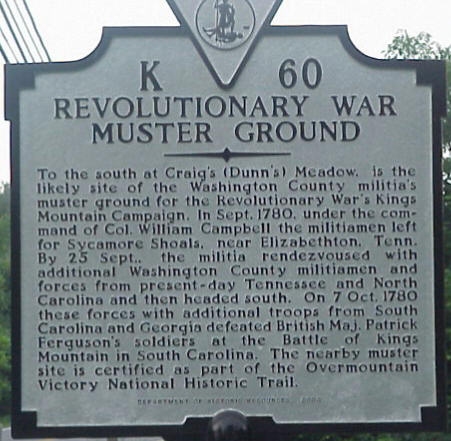

The 43-year-old Captain James Fulkerson joined with hundreds of other neighbors, including his brother, Abram, son-in-law, Benjamin Sharp and Samuel Vance, a future in-law, assembled in a field south of Abingdon (see pictures at right).

These "Overmountain Men" trekked to Elizabethton, North Carolina [now in Tennessee] where they rendezvoused with similar groups from the American backwoods. Then this volunteer army moved on into South Carolina, to seek out the British invaders, who were spearheaded by a company of Scots with faster-firing, breachloading rifles. An account of the campaign was published by his son-in-law Benjamin Sharp:

As well as I can remember, some time in August, in the year 1780, Col. McDowel of N. Carolina, with three or four hundred men, fled over the mountains to the settlements of Holstein and Watauga, to evade the pursuit of a British officer by the name of Ferguson, who had the command of a large detachment of British and Tories. Our militia speedily embodied, all mounted on horses, the Virginians under the command of colonel William Campbell, and the two western counties of North Carolina (now Tennessee) under the colonels Isaac Shelby and John Sevier, and as soon as they joined McDowel, he recrossed the mountains and formed a junction with Colonel Cleveland, with a fine regiment of North Carolina militia. We wore now fifteen or eighteen hundred strong , and considered ourselves equal in number, or at least a match for the enemy, and eager to bring them to Battle; but colonel McDowel, who had the command, appeared to think otherwise, for although Ferguson had retreated on our crossing of the mountains, he kept us marching and counter-marching for eight days without advancing a step towards our object. At 1ength a council of the field-officers was convened, and it was said in camp, how true I win not pretend to say, that he refused in council to proceed without a general officer to command the army, and to get rid of him, the council deputed him to general Green, at headquarters, to procure a general. Be this as it may, as soon as the council rose colonel McDowel left the camp and we saw no more of him during the expedition.

As soon as he was fairly gone the council reassembled and appointed colonel William Campbell our commander, and within one hour we were on our horses and in full pursuit of the enemy. The British still continued to retreat, and after hard marching for some time, we found progress much retarded by our footmen and weak horses that were not able to sustain the heavy duty. It was then resolved to leave the foot and weak horses under the command of captain William Neil, of Virginia, with instructions to follow as fast as his detachment could bear. Thus disencumbered we gained fast upon the enemy. I think on the seventh day of October, in the afternoon, we halted at a place called the Cow Pens, in South Carolina, fed our horses and ate a hearty meal of such provisions as we had procured, and by dark mounted our horses, marched all night and crossed the Broad River by the dawn of the day, and although it rained considerably in the morning, we never halted to refresh ourselves or our horses. About twelve o'clock it cleared off with a fine cool breeze. We were joined that day by Colonel Williams, of South Carolina, with several hundred men who informed us that they were just from the British camp, that they were posted on the top of King's Mountain, and that there was a picket-guard on the road not far ahead of us. These men were detained least they should find means to tell the enemy of our approach, and Colonel Shelby, with a select party undertook to surprise and take the picket; this he accomplished without firing a gun or giving the least alarm, and it was hailed by the army as a good omen.

We then moved on and as we approached the mountain the roll of the British drum informed us that we had something to do. No doubt the British commander thought his position was a strong one, but the plan of our attack was such as to make it the worst for him he could have chosen. The end of the mountain to our left descended gradually to a branch; in front of us the ascent was rather abrupt and to the right was a low gap through which the low road passed. The different regiments were directed by guides to the ground they were to occupy, so as to surround the eminence on which the British were encamped; Campbell's to the right, along the road; Shelby's next to the left of him; Sevier's next, and so on till last the left of Cleveland's to join the right of Campbell's, on the other side of the mountain at the road.

Thus the British major found himself attacked on all sides at once, and so situated as to receive a galling fire from all parts of our lines without doing any injury to ourselves. From this difficulty he attempted to relieve himself at the point of the bayonet, but failed in three successive charges. Cleveland, who had the farthest to go, being bothered in some swampy ground, did not occupy his position in the line until late in the engagement.

A few men, drawn from the right of Campbell's regiment, occupied this vacancy; this the British commander discovered, and here he made his last powerful effort to force his way through and make his escape; but at that instant Cleveland's regiment came up in gallant style; the colonel, himself, came up by the very spot I occupied, at which time his horse had received two wounds, and he was obliged to dismount. Although fat and unwieldy, be advanced on foot with signal bravery, but was soon remounted by one of his officers, who brought him another horse. This threw the British and Tories into complete disorder, and Ferguson seeing that all was lost, determined not to survive the disgrace; he broke his sword, and spurred his horse into the thickest of our ranks, and fell covered with wounds, and shortly after his whole army surrendered with discretion. The action lasted about one hour, and for most of the time was thick and bloody.

Marian Jackson

Marian Jackson

I cannot clearly recollect the statement of our loss, given at the time, but my impression now is that it was two hundred twenty five killed, and about as many, or a few more, wounded; the loss of the enemy must have been much greater. The return of the prisoners taken was eleven hundred and thirty three, about fifteen hundred stand of arms, several baggage wagons, and all their camp equipage fell into our hands. The battle closed not far from sundown, so that we had to encamp on the ground with the dead and wounded, and pass the night among groans and lamentations.

Thomas Jefferson commented on the battle,

I will remember the deep and grateful impression made on the minds of everyone by that memorable victory. It was the joyful enunciation of that turn in the tide of success which terminated the Revolutionary War with the Seal of Independence.

Jefferson's comment was not idle. It truly was the turning point. Before King's Mountain, troops in the north had experienced few victories and many retreats, and had been continually losing heart and deserting since 1776.

Major Ferguson threatened the Overmountain communities with burning and looting their homes if they didn't declare allegiance to Britain. The presence of British troops in the South had also encouraged Loyalist Tories and some Indians to engage in guerrilla activities and other forms of terrorism against the Carolina and Virginia patriot communities.

These Overmountain people, who in 1772 had formed the first independent civil government in the U.S. (the Wautaga Association, above) were not mild-mannered. Instead of preparing defenses for their communities, they headed across the mountains after Ferguson, chasing him to King's Mountain. American historian Bancroft described it this way:"The victory at King's Mountain changed the whole aspect of the War. The Tories no longer dared to rise. It fired the Patriots of the two Carolinas with fresh zeal. It encouraged the fragments of the defeated and scattered American army to seek each other and organize anew."

King's Mountain was one of the few battles the Americans actually won during the Revolution. One year later, in October 1781, the American army drove the British army into a hopeless position on a peninsula at Yorktown, Virginia, in a battle and seige that finally won America's independence from Britain.

After his return from the battle, James settled back into the business of being a farmer and landowner. Many other patriots in other communities might have reaped adulation, favor and political gains from their roles in such pivotal battles. In fact, James' role in the battle may have been crucial...historians tell us that Colonel Campbell was sidelined by diarrhea during the assault on the mountain, and that James succeeded in leading the men under his command against waves of counter-attacking British soldiers who threatened the outcome of the battle.

James and his neighbors knew what they'd accomplished. Had they come from a larger settlement or city their exploits might have been more deeply etched in America's memory, elevated to the same plane as Bunker Hill or Lexington and Concord -- all battles which we lost, by the way.

James and his neighbors returned to their isolated Overmountain communities, not to exult in their fame, but to live in the freedom which they'd helped to earn for themselves and their new nation.